Misinformation, False Narratives, and Bias in the Media

November 2021 | PDF version here

Introduction

Since Harris County’s misdemeanor bond system was first declared unconstitutional by a federal district court in 2017, the county has implemented several reforms as part of the resulting settlement. Before the resolution of the lawsuit, indigent defendants were detained pretrial solely based on their inability to pay bond, while their wealthier counterparts could post bond and expect prompt release. The county corrected this wealth-based discrimination by requiring the majority of misdemeanor defendants to be released on personal recognizance (PR) bonds, which do not require an upfront cash payment. By providing defendants with a new system for bonding out of jail that does not discriminate based on income, the implemented reforms ensure that defendants are not prematurely punished with jail time—upholding the principle of a ‘presumption of innocence’ for the criminally accused, and preventing taxpayers from footing the bill for unnecessary weeks or months of incarceration. Though these changes have only been applied to misdemeanor cases, several ongoing lawsuits have set the stage for reforms that could similarly improve the felony bond system. While these two systems are legally different, the rationale for reform remains the same: protecting constitutionally guaranteed rights and preventing wealth-based discrimination.

Despite the more equitable reforms to Harris County’s misdemeanor system, opponents of bond reform frequently criticize the changes. Though many opponents still claim to support the principles of reform, they regularly scapegoat bond reform for the various failures of the criminal legal system. Through the use of misinformation, propagation of false narratives, and exploitation of race-based disparities, they portray bond reform as a threat to public safety. Unfortunately, this disinformation effort is facilitated by local media outlets, who amplify the voices of opponents and disseminate the narratives they promote.

This report aims to examine media coverage of bond in Harris County, and to better understand the media’s role in shaping the narrative of bond reform. It draws on a content analysis of 226 news articles run by six Houston-area television stations between January 2015 and June 2021. Stories qualified for selection if they discussed bond reform, bond debates, and/or people who allegedly committed crimes while out on bond. While bias in coverage was the primary focus of this analysis, we also reviewed 15 other key variables, such as referenced ‘experts’ and the defendant’s race or ethnicity.

This analysis reveals that many local media stations disproportionately publish biased articles in their reporting on bond. The media consistently provide a platform for opponents of bond reform to represent bond release as a threat to public safety, while frequently failing to contextualize opponents’ claims or feature an alternative view. In cherry-picking and sensationalizing stories about defendants who are arrested while out on bond, media outlets construct a distorted narrative of dangerous releasees, in effect exaggerating the risks of bond reform and minimizing its positive impact. These efforts continually undermine bond reform, serving only to generate fear of people released on bond pretrial.

The shift in news coverage of bond is perhaps best seen through a comparison of coverage prior to and following the implementation of Harris County’s proposed settlement in 2019. Over the 48-month period from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2018, 42 total articles focused on bond in relation to reform or released defendants. Of those articles, only 33 percent were found to be negatively biased. In contrast, over a shorter 30-month period from January 1, 2019, to June 30, 2021, not only did the number of bond-focused articles more than quadruple to 184, but the percentage of negatively biased articles nearly doubled to 61.

Although bias in media coverage is one of the most—if not the most—alarming variables analyzed in this report, several other variables have revealed similarly concerning trends. With ongoing attacks against bond reform efforts in Texas and in Houston specifically, recognizing and correcting these trends in media coverage is critical to ensuring that Harris County residents have a more informed perspective of both misdemeanor bond reform and bond reform more generally.

Separating Arrest from Guilt

Just as bond is offered to those who are presumed innocent, all people who are arrested are considered innocent until proven guilty. However, one of the most common narratives in both society and the media is that most, if not all, people who are arrested will later be found guilty—a dangerous conflation of arrest with guilt, especially given that arrest predicates a person’s bond assignment. With much of the opposition to bond reform in the media relying on fearmongering that stems from this conflation, addressing misconceptions is a key part of refuting biased anti-reform narratives.

Many anti-reform arguments made by commentators in the media—which frequently go unchecked—point to the arrest of people out on bond as evidence that bond release enables more crime. They refer to such individuals as “repeat offenders” or even “career criminals” who should not have been released in the first place. This narrative fails to acknowledge that people who are accused of “reoffending” while out on bond have not been convicted, merely arrested; an arrest initiated their release on bond, and they were arrested again while out on bond. This distinction is important, as an arrest is by no means a direct path to conviction, nor is it a reliable indicator of guilt. Simply put, there are far more arrests than guilty convictions.

Moreover, given that over 90 percent of convictions are secured through guilty pleas, the ‘true’ number of convictions is likely lower than what is currently recorded.1 For an arrest to take place, law enforcement must identify a probable cause; conversely, guilty convictions that do not result from pleas only take place after the completion of a robust process involving the collection and scrutiny of evidence, investigations, and attempts by the prosecution to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Even when just considering differences in prerequisites, being found guilty is far different than simply being arrested.

Conflating arrest with guilt is particularly misguided in Harris County, which has a high case dismissal rate. To explain: One of the most common ‘conclusions’ to an arrest takes place far before the final decision of a judge or jury: dismissal of a case. A case may be dismissed for a number of reasons, but, in essence, a dismissal frequently indicates that the arrest was flawed or should not have taken place. The dismissal numbers in Harris County paint a different picture than the media would have you believe. In 2020, the Harris County District courts reported that there were nearly as many dismissals (8,270) as there were convictions (8,278).2 This problem seems to be getting worse through the first half of 2021, during which the Harris County District Courts have reported over 500 more dismissals than convictions.3

When considering this local context and the significant differences between arrest and guilt, arguing against bond reform on the basis of re-arrest during bond release is inherently flawed—and allowing such arguments to go frequently unquestioned in the media is as misinformed as it is misleading. Not only could a person’s arrest while on bond be later dismissed, but the original alleged charges leading to the bond assignment could themselves be dismissed.

SPOTLIGHT: Case Dismissals

Dismissals appear to be common among defendants whose cases are elevated by the media. We identified a total of 71 individuals who were named in our sample of articles; an analysis of their court records revealed that many of the charges highlighted by local media outlets were ultimately dismissed. Aggregating the charges of defendants in the sample whose cases were disposed, we found that 59 percent of pre-bond charges were dismissed, and 50 percent of post-bond charges were dismissed, with an overall dismissal rate of 55 percent. Among the 26 individuals whose pre-bond and post-bond cases were disposed, five had all charges dismissed. With only six individuals convicted on all charges, the remaining 60 percent had at least one of their charges dropped. Though some of these dismissals may have resulted from a defendant’s conviction on another charge, a look at the universe of Harris County court records suggests that this type of dismissal is quite rare: During the years 2019-2020, only 9.3 percent of all dismissals resulted from a conviction on another charge.

Methodology: Using the Harris County District Clerk’s online database, we looked up case records for each defendant identified in a news article as being on bond; we identified a total of 71 defendants who were named in the sample of articles. We then determined which charges were filed against each defendant before they were released on bond (“pre-bond charges”) and after they were released on bond (“post-bond charges”), using the publishing date of the news article as a reference. We identified post-bond charge(s) as any charge(s) filed against the defendant within 2 weeks of the article publishing date. We subsequently identified pre-release charges as the charge(s) filed against the defendant that chronologically preceded the post-release charge(s). In recording pre-bond charges, we included multiple charges if they were filed on the same date, but we did not include all charges filed against the defendant before their release on bond. We then noted whether each charge had been disposed or was still pending. If the case was disposed, we noted whether it was dismissed.

The Conflation of Reform

Although the only bond reform to have been proposed, approved, and implemented in Harris County applies to misdemeanor cases, its opponents frequently suggest that misdemeanor reform negatively impacts felony case processing—again resulting in false narratives about bond reform that are elevated by the media. In covering the issue of bond reform or a particular felony case, many articles fail to specify that reforms apply only to misdemeanor cases, and some even inaccurately suggest that felony bond reform has taken place. Conflation of this issue is perhaps best evidenced by articles that are primarily about bond reform, totaling 68 of the 226 articles we collected for this analysis. These articles directly address bond reform as an issue, and, relative to other articles that are centered around defendants, articles that are primarily about bond reform were found to be more frequently negative towards reform, with 78 percent of the articles identified as being negatively biased.

We analyzed all articles in this analysis for the type of bond they discussed, and we subsequently coded them as being about just misdemeanor or just felony, both misdemeanor and felony, or not about a specified type. Shockingly, almost half of the 68 articles primarily about bond reform—which one would expect to contain the most detail about the subject—did not specify which type of reform had been implemented. Moreover, more than a quarter of these 68 articles were about felony ‘reform’ (which has not taken place in Harris County), rather than about the actual reforms that have been approved. When viewing these classifications together, nearly 75 percent of all articles primarily about bond reform fail to mention the only reforms that have been considered and implemented in Harris County. The news media’s failure to make this distinction in their coverage is especially concerning because it is often accompanied by negative bias; among the 51 articles which failed to specify that reform has impacted only misdemeanor cases, 86 percent contain negative sentiment towards reform—a percentage even higher than that of the broader sample of articles primarily about bond reform.

The significance of this disparity in coverage across local television stations calls into question the stations’ ability to inform the public in a balanced way. By propagating an overwhelmingly negative portrayal of bond reform while failing to specify which type of reform is being discussed, some local media outlets are increasing the likelihood that the public will develop a negative association with existing misdemeanor reforms. Furthermore, the disproportionately large number of articles about felony ‘reforms’—which tend to rely on criticisms of bond reform in general, and which fail to even mention misdemeanor bond reform—run the risk of leading the public to conflate the two as essentially the same. Given that only misdemeanor reforms have been implemented in Harris County, this is clearly problematic, especially when considering that court-appointed independent monitors of the newly implemented reforms have found that successes have not come at the expense of “change[s] in reoffending” rates.4 Additionally, a recent review of Harris County court data revealed that 93 percent of people released pretrial later reappear for court hearings, indicating that the implementation of reform has not jeopardized the target outcomes of the bond system. Lastly, while proposals to fix the felony bond system that are built on reducing (and not increasing) pretrial incarceration, these proposals do not receive the same level of coverage as many regressive proposals, such as one passed by the Texas Legislature in September 2021, as evidenced by the disproportionate level of negative bias in coverage towards progressive reform. Without higher reporting standards that clearly specify and differentiate between existing policy and ongoing debates, the risk of conflating positive misdemeanor bond reform with often negatively portrayed or regressive ‘reform’ proposals will continue.

Bias and Its Sources

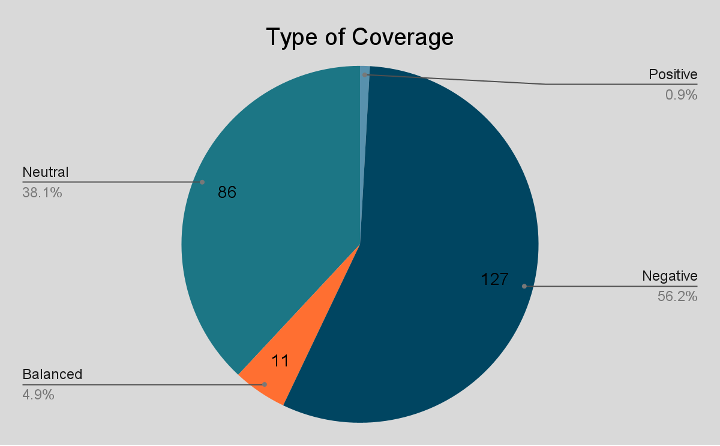

The sample of articles we collected for this analysis provide many insights into the frequency, content, and implications of biased media coverage. As displayed in the chart below, we coded over half of all news articles as negatively biased, with less than 1 percent considered positively biased. Even balanced coverage that maintains an impartial tone and offers equal space to both ‘sides’ of the bond debate—which one would presume to be the goal of the media—was found to comprise only 5 percent of the total coverage. Articles coded as “Neutral” were the second most common type, at about 38 percent of coverage; while this is certainly more desirable than negative alternatives, it still raises questions about the intentionality of local reporting on bond.

To be coded as “Neutral,” an article must have either lacked outside commentary and debate points or maintained a non-biased tone; in all but three neutral articles, this meant that articles would state that a person was out on bond at the time of an alleged crime, without any additional context for their bond. In such cases, the relevance of being out on bond is often questionable—particularly when considering that this does not account for the rates at which cases are dismissed or fail to lead to a guilty conviction—and could potentially lead to the perception that far more alleged crimes involve people out on bond than actually do. The consequences of a lack of balanced coverage raise separate concerns about the ability of local officials, particularly judges, to serve without fear of false attacks in the media. Ninety-four percent of all articles that mention judges by name were coded as negatively biased and frequently targeted individual judges for their bond decisions. While it is necessary to hold elected officials accountable for their decisions, accountability should not stem from misinformation. Given that both negative and neutral coverage pose significant problems, the lopsided nature of media coverage of bond reform in Harris County must be addressed and corrected.

Though many factors contribute to the imbalance in coverage, the use and selection of ‘expert’ references is particularly revealing; the two most commonly quoted sources in analyzed articles were law enforcement and Crime Stoppers, a local victims’ advocacy organization that is explicitly critical of bond reform. While these sources do provide information that can be considered relevant to many articles about bond, this often happens without additional information from other sources that may have different views. As a result, the testimony of law enforcement and Crime Stoppers is frequently framed as fact or undisputed, despite the commentary from each group having problematic elements.

Police and other law enforcement officials were cited in 141, or 62 percent of, reviewed news articles—typically to provide details about alleged crimes. Although this may initially seem logical, such an approach is flawed for a number of reasons. For example, as the ones who arrest people suspected of committing crimes, the police are at the front end of the legal process that arrested individuals undergo—a process that, as previously discussed, can deviate far from a guilty conviction and even end in dismissal. And when considering the high rate of dismissals in Harris County, the credibility of police as a definitive reference for what warranted an arrest is, at the very least, questionable. Former police chief Art Acevedo was referenced in 35 of these articles, 77 percent of which we coded as negatively biased coverage. With police being the most commonly referenced group by local stations in their bond coverage, this also raises doubts about articles being fairly framed.

Crime Stoppers is the second most frequent source for articles in our analysis, despite the group lacking the oversight and public accountability of a governmental group. It was referenced in a total of 76, or 34 percent of, all articles analyzed, usually via comment by Andy Kahan, the group’s Director of Victim Services and Advocacy; alarmingly, all but one of these articles contained negative bias. Crime Stoppers is also referenced in half of all articles that are primarily about bond reform, suggesting that quotes from the organization are central in bolstering the overwhelmingly negative coverage of reform. Despite the problems related to conflating arrest with guilt, Kahan and Crime Stoppers frequently do so when providing commentary to the media, and they often directly criticize bond reform.5 Among other things, Kahan has insinuated that misdemeanor bond reform has led to a spike in homicide rates,6 pointing to the “bond pandemic” as responsible for the death of a sheriff’s deputy and others.7 In more than 40 percent of the articles that reference Crime Stoppers, the type of bonds being discussed is not specified—meaning that any criticism of existing bond reform does, by default, refer to misdemeanor bond reform. Kahan was not identified as a reference in any of the articles run by the two Spanish-language stations, KXLN and KTMD, and Crime Stoppers as an organization was only referenced in one of their articles.

While the police and Crime Stoppers are the two most referenced groups among local news, we also identified police unions and the Harris County District Attorney’s Office as two groups that may become relatively common sources. Given that police unions are uniquely positioned to share in the flaws of both police and non-governmental groups, referencing them is a point of concern—though only 17 articles in our analysis included commentary from a police union or their spokesperson, 94 percent of which were coded as negatively biased.

The messaging from Crime Stoppers and the police union aligns with that of District Attorney Kim Ogg (who served as Executive Director of Crime Stoppers of Houston from 1997-2006) and her office, which has been clearly and consistently against pretrial release. Referenced in 53 articles, 23 percent of the sample, the District Attorney’s Office is not cited as frequently as police; however, like police, the District Attorney’s office is frequently framed as an authoritative source on criminal cases despite its stake in the adversarial process of prosecuting defendants. Accordingly, we found that 62 percent of the 53 articles referencing the District Attorney’s Office were negatively biased. Further, 71 percent of the articles referencing District Attorney Kim Ogg were negatively biased, though she was only quoted in a total of 14 articles. For the sake of balanced reporting, it would be best for the number of articles citing these sources to remain low or for counter-perspectives to be included in any article referencing them.

Overall, regarding news articles including any of the four above sources, we coded at least 50 percent as negatively biased. In recognizing this level of bias with each of the issues surrounding these sources, we must question the willingness of local media to rely on such references, as well as question which groups are being positioned to push narratives throughout Harris County.

SPOTLIGHT: Crime Stoppers

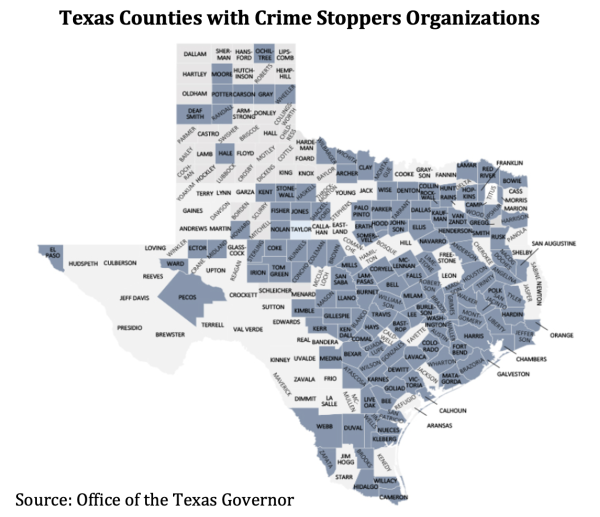

A review of Texas law suggests that Crime Stoppers Houston is financially incentivized to generate fear of crime, as the organization has a financial stake in churning people through the criminal legal system. Local Crime Stoppers corporations routinely receive funds from criminal courts as authorized by Chapter 414 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.8 The Texas Crime Stoppers Council, under the Office of the Texas Governor, certifies local Crime Stoppers affiliates as eligible to receive funds from courts in order to pay rewards to tipsters. Crime Stoppers Houston is one of 150 certified Crime Stoppers organizations in Texas, though the Houston affiliate claims to be one of the largest organizations in the country.

A review of Texas law suggests that Crime Stoppers Houston is financially incentivized to generate fear of crime, as the organization has a financial stake in churning people through the criminal legal system. Local Crime Stoppers corporations routinely receive funds from criminal courts as authorized by Chapter 414 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.8 The Texas Crime Stoppers Council, under the Office of the Texas Governor, certifies local Crime Stoppers affiliates as eligible to receive funds from courts in order to pay rewards to tipsters. Crime Stoppers Houston is one of 150 certified Crime Stoppers organizations in Texas, though the Houston affiliate claims to be one of the largest organizations in the country.

According to the Texas Local Government Code, Crime Stoppers receives 0.2427 percent of all court costs collected from convicted criminal defendants.9 In addition to receiving a portion of all court fees, Crime Stoppers is also the sole recipient of a fine of up to $50, which may be required of defendants who are placed on probation. Further, a judge can order that a defendant who is placed on probation reimburse Crime Stoppers for the reward amount paid to the tipster whose tip led to the defendant’s arrest and conviction. The funds that Crime Stoppers receives through these channels are intended to be used as reward payments for those who provide tips to the organization, but state law allows 20 percent of the funds to go towards administrative spending.10

In 2019, Crime Stoppers Houston reported a revenue of $114,616 from “court rewards” and $30,427 from “court administrative funds.” In 2020, these revenue streams dropped to $63,494 and $15,923 respectively.11 In October 2020, KTRK reported that Crime Stoppers Houston was “running low on reward money for [the] first time.”12 Crime Stoppers Houston CEO Rania Mankarious cited the decrease in court funds over the previous two years, blaming judges for no longer requiring probationers to pay the Crime Stoppers fee. A week later, Andy Kahan (Crime Stoppers’ Director of Victim Services and Advocacy) appeared at Harris County Commissioners Court to support a motion from Commissioner Jack Cagle (a Crime Stoppers donor13) to have the county partner with Crime Stoppers to release a report showing the impact of bond reform on crime victims. County Judge Lina Hidalgo rejected the motion, arguing that the county should not partner with interested organizations that have “an axe to grind.” The following month, Crime Stoppers Houston partnered with KRIV (the FOX affiliate) to launch the ‘Breaking Bond’ series. These coinciding events raise the possibility that Crime Stoppers escalated its fearmongering efforts in response to a shortage of funds.

Reality vs. Media Coverage

Beyond just the implications for reform efforts, local media coverage in Harris County often involves a racialized narrative of criminality and a distortion of the kinds of alleged offenses actually taking place. We collected demographic and offense data from a total of 158 articles that were primarily about defendants and the alleged crimes they were accused of committing while out on bond; since Harris County does not record defendants’ ethnicity, we could only record their race. Across all media stations, 49 percent of articles focused on at least one Black defendant, 47 percent focused on at least one white defendant, 4 percent focused on defendants whose race was unknown, and no articles focused on Asian or Indigenous defendants. Like in many other areas of the criminal legal system, these figures are not representative of the broader population, and, in terms of people released pretrial, these percentages are also misleading.

When specifically looking at pretrial data collected from January 1, 2019, to April 13, 2021, Black defendants are over-represented in various ways. Among articles run by the media during this timeframe, 64 percent of covered defendants out on bond were Black, compared to the 41 percent that were actually out on bond overall—a figure that is, itself, also unrepresentative of the broader population of Harris County; according to Census Bureau estimates from 2019, only 20 percent of Harris County residents were Black or African American.14 Given that almost 85 percent of stories in this sample—and even among all articles discussing defendants—include mugshots, viewers of local media are frequently exposed to coverage that disproportionately portrays Black residents of Harris County as those who allegedly commit crimes while out on bond.15

Separately, given that Harris County does not further disaggregate the percentage of white defendants into categories of white alone or white and Hispanic, the percentage of minority defendants covered by the media is likely far higher than what is currently shown by the data, especially when considering that the Census Bureau has estimated that only 29 percent of Harris County residents are white and not Hispanic.16

According to media coverage, the offenses themselves are also not representative of the crimes that have allegedly taken place among those out on bond. Per articles from January 2019 to April 2021, 67 percent of defendants were allegedly involved in homicides in some way;17 this could include a past offense, an offense that led to a bond assignment, or, most importantly, an offense that was allegedly committed while out on bond. But with less than 1 percent of offenses allegedly committed by those out on bond actually related to homicide, the percentage of articles focused on homicide cases is clearly significantly higher than the actual rate of recorded charges for those out on bond. While these types of offenses are often more ‘sensational’ or considered more newsworthy than other, more common offenses allegedly committed on bond, such as those related to controlled substances, over-coverage of homicides runs the risk of distorting reality—especially when also considering the racial aspects of this coverage.

Conclusion

Though misdemeanor bond reform in Harris County has led to many positive improvements—protecting people’s constitutionally guaranteed rights, preventing wealth-based discrimination, and reducing taxpayer costs—these gains have not been mirrored in local media coverage. If anything, the media actively misrepresents the impact of bond reform through the conflation of separate concepts, promotion of unreliable ‘experts,’ and reliance on statistics that do not reflect reality. In addition to being problematic in and of themselves, current reporting practices have also been used in part of a broader push to tie bond reform to an increase in crime in Houston and Harris County (an increase seen across Texas, even in places without bond reform).18 As Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg stated during her testimony before the Texas Legislature in spring 2021, “crime is up, ladies and gentlemen, and it is associated with bail.”19

Unfortunately, the nuances of this issue have been relatively unaddressed by local media in comparison to the narratives favored by opponents of bond reform. It is worth noting, however, that these trends are not presented uniformly by each individual news station; for example, in comparison to 85 percent of KRIV's coverage being identified as negatively biased against reform, less than 50 percent of KPRC’s coverage was found to be similarly biased. Differences in coverage were also apparent when comparing the four primarily English-language stations to the two primarily Spanish-language stations. Just by viewing the difference in number of stations, one would expect more articles to be run by the English-language stations. And in fact, not only did the Spanish-language stations run fewer total articles, but they also ran only 11 percent of all articles combined. Since the beginning of 2015, no Spanish-language station ran more than 15 articles about this subject, while each English-language counterpart ran at least 30 articles.

This disparity prompts questions about the validity of claims that bond reform is a pressing issue for Harris County and the city of Houston. The causes for the disparity could be as simple as a difference in what is regarded as interesting to viewers or ‘profitable’ as news. Conversely, when considering that Spanish-language stations referenced Crime Stoppers just once—and police unions not at all—perhaps they do not receive outreach from these groups or choose not to elevate their false narratives. Regardless of the ultimate reason for these differences in coverage, residents of Harris County should reflect on the quality of reporting from whichever station they trust to provide them with news—especially since, as a whole, the media seems interested in telling only one side of the story.

Methodology

We conducted a content analysis of 226 news articles run by six Houston-area television stations from January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2021. While bias in coverage was the primary focus of this analysis, we also reviewed 15 other key variables, such as referenced ‘experts’ and the defendant’s race or ethnicity. Listed below are additional details about each element of the analysis.

Sample

We selected news articles for this analysis from six television stations, four of which—KPRC, KTRK, KHOU, and KRIV—primarily provide news coverage in English, and two of which—KXLN and KTMD—primarily provide news coverage in Spanish. We found articles using a three-step process: first, we searched for bond topics on each station’s website; second, we searched for bond topics for each station on google while filtering by “News” and year; third, for each article that named an individual(s), we searched their name(s) in both each news station’s website and on google to find follow-up articles. Stories qualified for selection if they discussed bond reform, bond debates, and/or individuals who allegedly committed additional crimes while out on bond; stories were not qualified for selection if they simply mentioned bond assignments in high-profile cases. While this sample is composed of only digitally-available content, we only selected articles for review, and not photo or video reports.

KPRC - NBC Affiliate

A total of 52 articles ran from 07/14/2015 to 06/10/2021. We identified but did not include republished Texas Tribune and AP articles, and we did not find any special segments related to this subject.

KTRK - ABC Affiliate

A total of 61 articles ran from 02/13/2015 to 06/21/2021. We identified but did not include republished Texas Tribune articles, and we did not find any special segments related to this subject.

KHOU - CBS Affiliate

A total of 34 articles ran from 02/16/2015 to 06/23/2021. We identified but did not include republished Texas Tribune articles, and we did not find any special segments related to this subject.

KRIV - FOX Affiliate

A total of 54 articles ran from 07/27/2015 to 06/29/2021. We identified but did not include republished AP articles, and we found and included a special segment about bond, Breaking Bond.

KXLN - Univision Affiliate

A total of 13 articles ran from 11/12/2020 to 06/27/2021. We did not identify any republished articles, and we did not find any special segments related to this subject.

KTMD - Telemundo Affiliate

A total of 12 articles ran from 08/07/2019 to 06/16/2021. We did not identify any republished articles, and we did not find any special segments related to this subject.

Coding

A team of 10 people participated in coding each of the variables for every article; each person was assigned to code articles in one of four groups of variables. Additionally, each person attended at least one briefing on the coding process and received access to a coding guide for reference; coders were also provided opportunities to ask questions, if necessary. We considered 16 variables as key for the analysis, while 5 others were used to provide logistical information. Once the initial coding process concluded, we audited the variables for accuracy.

Key Variables

- “Primarily Bond Reform” refers to whether or not the focus of each article’s content was primarily about bond reform. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” Coding an article as “Yes” indicates that it is primarily about bond reform and that a majority of the article’s focus is on bond reform, not on a defendant. Coding an article as “No” indicates that it is primarily about a defendant who allegedly committed a crime while out on bond. This variable is part of Group 1.

- “Type of Coverage” refers to the type of bias in an article, if any. Coding Terms for this variable include: “Positive,” “Negative,” “Balanced,” and “Neutral.” Coding an article as “Positive” or “Negative” depended on the overall article tone, on which outside sources were used to provide commentary in the article, and which ‘side’ of the bond reform debate received more space in the article. Articles coded as “Positive” indicated a positive bias (in favor of bond reform), while those coded as “Negative” indicated a negative bias (against bond reform). The presence of bias does not necessarily reflect an internal check for inaccurate information—though negative bias often overlaps with the use of inaccurate information. If the article maintained a neutral tone and offered equal space to both ‘sides’ of the debate, we coded it as “Balanced.” If the article mentioned bond reform or defendants who allegedly committed a crime while out on bond without providing outside commentary, debate points, or a slanted tone, we coded it as “Neutral.” Given the differences in content between the two article types, “Balanced” was overwhelmingly coded for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” while “Neutral” was overwhelmingly coded for articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; “Positive” and “Negative” were equally applicable to both article types. This variable is part of Group 1.

- “Law Enforcement Referenced” refers to whether or not a law enforcement official is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 1.

- “CS/Kahan Referenced” refers to whether or not Crime Stoppers (CS) or one of their spokespeople—specifically Andy Kahan—is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. We did not select articles that simply mentioned or included the name Crime Stoppers or their tip line. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 1.

- “Police Union Referenced” refers to whether or not a police union—or other law enforcement union—or one of their spokespeople is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 3.

- “Mention Statistics” refers to whether or not statistics or figures are mentioned in an article’s commentary or characterization of bond. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 1.

- “Mention Judges” refers to whether a local district or felony court judge(s) is mentioned by name in the article. We did not consider federal judges or county judges. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Judge’s Name]” and “Unmentioned.” This variable is part of Group 3.

- “Mention Homelessness” refers to whether or not homelessness is mentioned as a relevant detail in the article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 3.

- “Mugshot/Picture Included” refers to whether or not a mugshot(s) or mugshot-like picture(s) is used in the article; this can include an embedded image, video thumbnail, or use of a mugshot by the station in an embedded video. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” This variable is part of Group 2.

- “Misdemeanor/Felony” refers to the kind of crime/bond explicitly mentioned and/or the primary focus of the article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Misdemeanor,” “Felony,” “Both,” and “Unmentioned.” Coding an article as “Misdemeanor” or “Felony” indicates that the article only discusses either misdemeanors or felonies by name. “Both” indicates that both misdemeanors and felonies are discussed. “Unmentioned” indicates that neither misdemeanors nor felonies are specified and that the type of bond being discussed is ambiguous. This variable is part of Group 4.

- “Defendant Name” refers to the name of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Defendant’s Name],” “Unknown,” and “N/A.” We only considered names in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Name” as “N/A.” For articles about multiple defendants, we coded defendants who were not out on bond as “N/A.” This variable is part of Group 2.

- “Defendant Race/Ethnicity” refers to the race or ethnicity of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “White,” “Non-White,” “Unknown,” and “N/A.” After the initial coding, we searched for defendants by name on the Harris County District Clerk’s website to confirm their recorded race; Harris County does not record defendant ethnicity, so only race was used. Following confirmation, coding terms include: “Asian,” “Black,” “Indigenous,” “White,” “Unknown,” and “N/A.” We only considered race in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Race/Ethnicity” as “N/A.” For articles about multiple defendants, we coded defendants who were not out on bond as “N/A.” This variable is part of Group 2.

- “Defendant Sex” refers to the sex of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Male,” “Female,” “Unknown,” and “N/A.” We only considered sex in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Sex” as “N/A.” For articles about multiple defendants, defendants who were not out on bond were listed as “N/A.” This variable is part of Group 2.

- “Defendant Bond” refers to the kind of bond that was received by the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Paid,” “Unpaid,” “[Bond Name],” “Both,” “Unmentioned,” and “N/A.” If applicable, we coded multiple bond types. “Paid” refers to a bond that required a payment from the defendant, whereas “Unpaid” refers to a bond that did not require a payment, such as a PR bond. We only considered the kind of bond in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Bond” as “N/A.” This variable is part of Group 4.

- “Defendant Offense” refers to the offense that was allegedly committed by the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. The alleged offense can refer to a past offense, the offense that led to a bond assignment, or the offense that the defendant(s) may have committed while out on bond. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Offense Name],” “Unclear,” “N/A (suspect killed by police),” and “N/A.” We only considered the offense in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Offense” as “N/A.” This variable is part of Group 4.

- “Defendant Characterization” refers to characterizations of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article that may reflect case details, such as mental health, or may reflect false narratives, such as conflating arrest with guilt. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Type of Characterization],” “None,” and “N/A.” We only considered characterizations in articles coded as “No” for “Primarily Bond Reform”; for articles coded as “Yes” for “Primarily Bond Reform,” we coded “Subject Characterization” as “N/A.”

Other Variables

- “Article Link”

- “Television Station Name”

- “Reporter Name(s)”

- “Publishing Date”

- “Notes” provides a chance for coders to note any unique article details or requests for other coders.

1 Texas Office of Court Administration, Judicial Activity Reports.

2 Id.

3 Id. From January 1 – June 30, 2021, Harris County reported 6,447 dismissals and only 5,923 convictions.

4 Jolie McCullough, “Report: Harris County’s bail reforms let more people out of jail before trial without raising risk of reoffending,” Texas Tribune, September 3, 2020.

5 Crime Stoppers Houston, “The Revolving Door at the Courthouse and Rising Crime Rates,” Bail Reform, January 4, 2021.

6 Randy Wallace, "Breaking Bond: Opponent to felony bond reform in Harris County speaks," FOX 26 Houston, May 19, 2021.

7 Phil Archer, "Suspect accused of shooting Harris County deputy was free on multiple bonds," Click2Houston, January 27, 2021.

8 Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Chapter 414: Texas Crime Stoppers Council, Sec. 414.010.

9 Texas Local Government Code, Chapter 133: Criminal and Civil Fees Payable to the Comptroller, Sec. 133.102.

10 Office of the Texas Governor, Texas Crime Stoppers Certification Process.

11 Crime Stoppers of Houston, Inc., Financial Statements and Independent Auditors’ Report for the years ended December 31, 2020 and 2019.

12 Courtney Fischer, “Houston Crime Stoppers running low on reward money for first time,” KTRK ABC 13, October 20, 2020.

13 Crime Stoppers of Houston, Annual Report 2020, pp. 32-33.

14 United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Harris County, Texas,” July 1, 2019.

15 See “The Mug Shot, a Crime Story Staple, Is Dropped by Some Newsrooms and Police" (2020) for more information on the history and debates surrounding the usage of mugshots.

16 United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Harris County, Texas.”

17 Further review of these cases showed that 46% of defendants were charged with a homicide-related offense, suggesting that stories related to homicide are published multiple times OR not all defendants are actually charged with homicide offenses.

18 Grits for Breakfast, "Murders in Texas increased 37% statewide in 2020, with Republican-led communities suffering the biggest spikes. But overdose deaths doubled murders. Are we focused on the wrong problems?," July 22, 2021.

19 Randy Wallace, “Shocking statistics revealed during Senate hearing for bill aimed at stopping repeat violent offenders,” FOX 26 Houston, March 18, 2021.