How the Houston Chronicle's Coverage of Bond Misinforms the Public

April 2022 | PDF version here

Introduction

The media performs a powerful role in the policy arena, not simply because its reporting informs the public, but because its editorial decisions have the potential to influence public opinion and determine which issues capture the public’s attention. In this report series, we explore the role of local Houston media outlets in shaping the narrative of bond reform.

To provide some background: Since Harris County’s misdemeanor bond system was first declared unconstitutional by a federal district court in 2017, the county has implemented several reforms as part of the resulting settlement. Before the resolution of the lawsuit, indigent defendants were detained pretrial solely based on their inability to pay bond, while their wealthier counterparts could post bond and expect prompt release. The county corrected this wealth-based discrimination by requiring the majority of misdemeanor defendants to be released on personal recognizance bonds, which do not require an upfront cash payment. By providing defendants with a new system for bonding out of jail that does not discriminate based on income, the implemented reforms ensure that defendants are not prematurely punished with jail time—upholding the principle of a ‘presumption of innocence’ for the criminally accused, and preventing taxpayers from footing the bill for unnecessary weeks or months of incarceration. Yet despite the more equitable reforms to Harris County’s misdemeanor system, opponents of bond reform frequently criticize the changes.

In Part I of this report series, we analyzed the impact of six Houston-area television stations, demonstrating that these outlets consistently provided a platform for opponents of bond reform to frame pretrial release as a threat to public safety, both through the propagation of false narratives and the exploitation of race-based disparities. In Part II, we turn to newspaper media, aiming to understand the Houston Chronicle’s coverage of bond. This report draws on a content analysis of 499 news articles published by the Chronicle between January 2015 and December 2021. Stories qualified for selection if they discussed bond reform, bond debates, and/or people who allegedly committed crimes while released on bond.

In the context of Harris County bond policies, the media contributes to the local discourse on bond in two major ways: 1) through its coverage of bond reform, which informs the public about the impetus for reform and the debates surrounding bond-related policy changes, and 2) through its coverage of crime, which concretizes these policy discussions by drawing the reader’s attention to specific cases involving bond. Through our analysis, we found that the Houston Chronicle provided balanced and informative coverage of bond reform, but the newspaper sacrificed its impartiality by disseminating negative coverage of legally innocent defendants who were rearrested while released on bond.

The Chronicle can be commended for its balanced coverage of bond reform itself, but the impact of its biased crime coverage on the bond reform discourse should not be underestimated. Research demonstrates that much of the general public’s understanding of crime comes from consumption of mass media. Because the media has the discretion to determine which crime stories are newsworthy, the criminal cases elevated in the media are usually the most extreme, statistically rare cases, selected to capture the public’s attention. As a consequence of this disproportionate coverage of the most sensational cases, the public gains a distorted perception of crime that leads to heightened fear of victimization. In the context of bond, this distortion is achieved through the coverage of stories about a defendant rearrested for a violent crime while released on bond. Although such an occurrence is statistically rare, its frequency is exaggerated in crime coverage, which has the effect of generating public fear of pretrial release. Crime coverage, therefore, has just as much potential to inform the public’s perspective on bond reform as news coverage that directly addresses bond policies.

Though the Chronicle’s crime coverage undeniably impacts the public’s perception of bond release, our analysis demonstrates that this coverage does little to inform the public about the arrest, bond, and case dismissal process. Our review of the criminal cases covered by the Chronicle reveals that many had not reached a disposition at the time of our analysis; it also reveals a high proportion of case dismissals among the cases that did reach a disposition. The high proportion of unresolved and dismissed cases shows these stories focus on unproven criminal allegations rather than convictions—calling into question the utility of reporting on criminal cases prematurely. Criminal allegations are necessarily speculative and uncertain, and covering them requires reliance on the narratives of law enforcement and prosecutors, sources incentivized to insinuate guilt. Further, the strict coverage of arrests (versus actual case outcomes) results in a distorted and therefore misleading portrayal of crime and the criminal legal system.

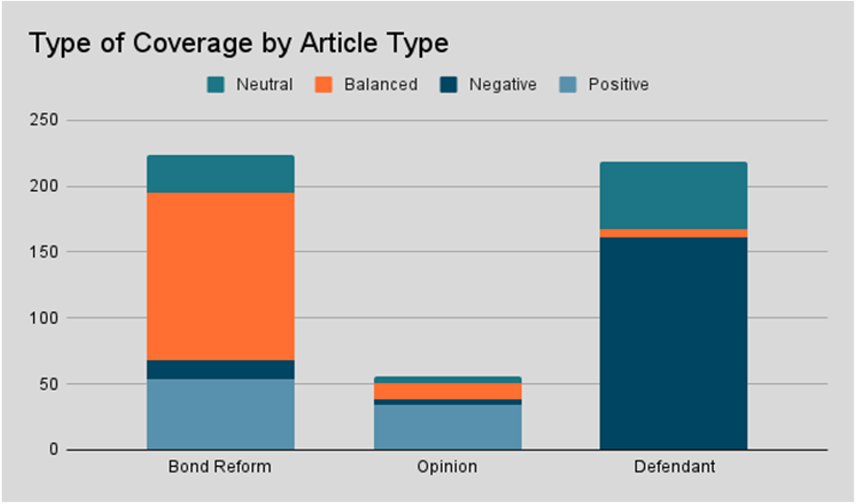

Divergence in Coverage: Balanced vs. Biased

The Houston Chronicle’s coverage of bond is characterized by two diverging narratives. While the Chronicle consistently provided balanced coverage of bond reform issues and published positive endorsements of bond reform via its editorial board, the paper simultaneously distributed overwhelmingly negative coverage of defendants who were released on bond. We divided our sample of articles about bond into three types: 1) articles about bond reform, bond policies, or bond practices; 2) opinion articles that discuss the topic of bond; and 3) articles about defendants who were released on bond. The level of bias that we identified in the Chronicle’s coverage of bond was highly dependent on article type, with bond reform articles coded as 57 percent balanced and 25 percent positive, opinion articles as 23 percent balanced and 61 percent positive, and defendant articles as 24 percent neutral and 74 percent negative.

The majority of the Chronicle’s reporting on bond reform was balanced coverage, with 57 percent of 224 bond reform articles coded as balanced. We coded an article as “balanced” if it maintained a neutral tone about bond reform (or pretrial release in general) and offered perspectives from both sides of the bond reform debate. We included in our sample any articles that discussed bond as a policy issue, including articles about judges’ bond practices, attempts to address jail overcrowding, and releases in response to COVID-19; however, the majority of articles in the ‘bond reform’ subsample were about the O’Donnell lawsuit—the previously referenced class action suit which alleged that Harris County’s misdemeanor bond system was unconstitutional. Throughout the duration of the O’Donnell litigation, the Chronicle published mostly balanced coverage of bond reform that included perspectives from both sides of the lawsuit. Between May 2016 and November 2019, the period when the lawsuit was pending, the Chronicle published 148 articles about bond reform or other policy issues related to bond. These articles were 55 percent balanced, 28 percent positive, 13 percent neutral, and 3 percent negative. Reporting on pending litigation lends itself naturally to balanced coverage, as a lawsuit inherently involves two opposing perspectives: the plaintiffs and the defendants. We coded nearly a third of articles as positively biased because they leaned more heavily towards the perspective of the plaintiffs and supporters of bond reform.

SPOTLIGHT: Positive vs. Negative Bias

In evaluating the Houston Chronicle’s coverage of bond, we characterize “bias” as a journalistic shortcoming because it represents a slant in coverage that violates the media’s purported impartiality. Though we commend balanced coverage as the ideal standard of reporting, we nevertheless acknowledge that the nature and content of articles containing positive bias were vastly different than those of negatively biased articles. In the context of coverage of bond, negatively biased articles were often rooted in misinformation, fearmongering, and a distortion of reality. Positively biased articles, on the other hand, often entailed an accurate endorsement of the impetus for bond reform—namely, the unconstitutionality of the county’s preceding bond system—but were labeled as “biased” because they did not include the perspective of the opposing side of the bond reform debate. Rather than applaud coverage supportive of bond reform, we emphasize the harmful impact of negatively biased coverage that relies on speculative reporting and interested sources, and that fails to follow a case through disposition.

In addition to offering balanced news coverage, the Chronicle conveyed a supportive stance towards bond reform in Harris County through its published opinion articles. Though these articles were less numerous than the other two article types, representing just 11 percent of our sample [56 total articles], we coded 61 percent as positively biased. Half of these positive opinion articles were authored by the Chronicle’s Editorial Board. Editorials, of course, are not bound to the same journalistic standards as news stories and are thus more deliberately biased in favor of one side of the bond debate. For the purposes of our analysis, the “bias” in published opinion articles does not indicate a journalistic shortcoming; rather, it communicates to the Chronicle’s readers a stance in the bond reform debate. Regardless of whether the paper would claim the opinions of its editorial staff as an official stance, its editorials have the impact of communicating a stance to the reader.

In contrast to its largely balanced or positive coverage of bond reform, the Chronicle’s coverage of defendants who were rearrested while released on bond was predominantly negative. Of the 219 ‘defendant’ articles in our sample, we coded 74 percent as negatively biased. We coded an article as “negatively biased” if it framed pretrial release negatively, mentioned a defendant’s release on bond without context, or conflated arrest with guilt. In addition to the negative bias found within the majority of defendant articles, we argue that much of the negative impact of these stories stems from the Chronicle’s appraisal of this type of story as newsworthy. By choosing to cover stories about defendants who are rearrested for violent crimes while released on bond—an occurrence that, as we detailed in our previous report, is statistically rare among released defendants—reporters call attention to bond release as having negative consequences. In other words, in repeatedly linking bond release to subsequent criminal allegations, the Chronicle exaggerates the risks of pretrial release, promoting a narrative of bond reform that reinforces the arguments of opponents of bond reform.

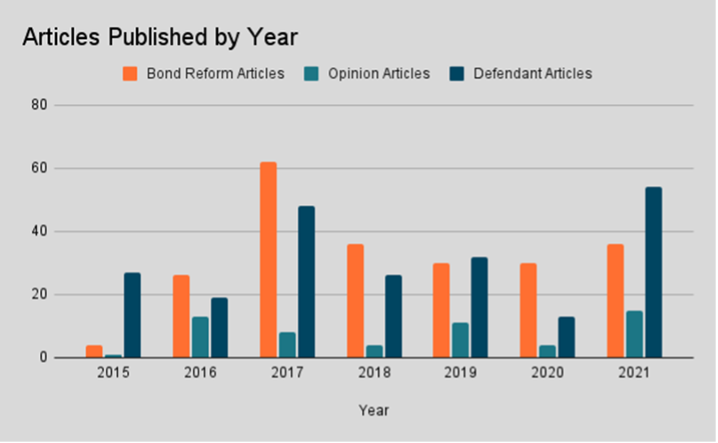

Bond reform articles and defendant articles made up similar proportions of our sample, at 44.9 percent and 43.9 percent respectively. Though the total number of bond reform and defendant articles were similar, disaggregating the number of articles published by year reveals an inconsistent distribution of articles across the sample period. The number of bond-related articles published over time appears to reflect shifts in the local discourse surrounding bond reform, particularly driven by the O’Donnell lawsuit and the later bond “reform” bills introduced during Texas’ 2021 legislative session. One would expect the number of bond reform articles to be influenced by these events, but the graph below reveals the extent to which the number of articles published about released defendants also appears to be driven by the local political context. In 2015, before the O’Donnell lawsuit was filed, defendant articles were far more numerous than bond reform articles; in 2016, when the bond lawsuit was filed, the number of articles written about bond reform increased dramatically. During the lawsuit, however, both article types shifted at similar rates, suggesting that editorial decisions about defendant articles were also influenced by the ongoing litigation. Interestingly, defendant articles dropped off dramatically in 2020 following the O’Donnell settlement, which led to the implementation of misdemeanor bond reform in Harris County. Then, in 2021, the number of defendant articles published increased by 315 percent with the onset of the legislative session and discussion of regressive bond “reform” bills. The decrease in defendant articles in 2020 followed by the dramatic increase in 2021 supports the notion that the Chronicle’s publishing of defendant articles was motivated by the political climate, not the increase in pretrial releases following misdemeanor bond reform.

Taken together, the Chronicle’s balanced if not positive coverage of bond reform is in effect canceled out by its negative coverage of released defendants. Coverage of legally innocent defendants who are accused of crime while released on bond draws a link between bond release and dangerousness, an association that generates fear of pretrial release. Despite the Chronicle’s balanced coverage of bond reform, appeals to emotion are more impactful than appeals to reason. As a result, the fear-based coverage of “dangerous” releasees likely resonates with readers more than the logic-based coverage of bond reform. Opponents of bond reform frequently rely on cherry-picked stories of defendants who are rearrested for violent crimes in their anti-bond reform rhetoric, and they aim to characterize these events as ubiquitous and threatening. By elevating these stories, the Houston Chronicle is complicit in this misinformation campaign. Though the Chronicle elevated arguments supporting pretrial release in its coverage of bond reform, we could find few examples of defendant stories that included perspectives from those supportive of bond reform or concerned for the constitutional rights of the accused. This inconsistent messaging suggests that the Chronicle is willing to sacrifice balanced, informative coverage in favor of sensationalist stories designed to generate a reaction.

That a roughly equal number of articles were written about defendants accused of additional crimes while released on bond as those written about bond reform, practices, and policies amidst a historic bond lawsuit and settlement suggests that the Houston Chronicle deems these topics equally newsworthy. In the next section, we will explore why the Chronicle’s reporting on released defendants poses questions about newsworthiness.

Questionable News Value: A Focus on Unproven Allegations

The bulk of articles published about defendants released on bond involve arrests or allegations emerging from the front end of the criminal process. The Houston Chronicle ostensibly covers these “breaking crime” stories to inform the public. A closer look at the content of these stories, however, calls into question whether they provide any news value whatsoever.

Routinely, articles covering an accused defendant detail the individual’s criminal history, including past arrests, and often emphasize their bond status. In focusing attention on these details, reporters imply that a previous arrest or release on bond indicates something about the defendant’s guilt or criminality. Given that defendants who are released on bond have merely been arrested for, not convicted of, a charge, it is inappropriate to attach assumptions of guilt or dangerousness to them. Being rearrested while released on bond does not indicate that a person is particularly prone to criminal activity; rather, it indicates that they have been accused of more than one crime. Because each defendant enjoys innocence until proven guilty, an individual’s history of arrests, particularly in absence of a conviction, is not relevant to a subsequent case. Multiple bonds or multiple arrests are more likely to indicate that a person lives in an over-policed community than that they are especially guilty.

Understanding the detrimental impact of this type of biased coverage requires an understanding of how criminal charges are filed in Harris County. This process begins when allegations of wrongdoing are written into a complaint filed by the District Attorney’s Office. These complaints are, by definition, just allegations, and the remainder of the disposition process for a criminal case focuses on determining the truth or falsity of those written allegations. At this point in the process, the standard for whether a criminal complaint proceeds is a determination of probable cause, which exists “…when the facts and circumstances within the arresting officer’s knowledge, and of which he has reasonably trustworthy information, are sufficient to warrant a prudent man in believing that the person arrested had committed or was committing an offense.” Note that all that is required at this point is belief that an offense was committed, and that the truth or falsity of the charges remains to be determined.

The system accounts for the ambiguity of the probable cause standard by increasing the scrutiny of criminal allegations as the case proceeds—first through a phase called discovery, wherein the police and prosecutors are required to produce any evidence that may be exculpatory to the defendant; then, assuming charges have not already been dismissed or the defendant has not entered a plea, the case is given to the fact finder (either a judge or a jury) for determination of guilt. Each element of any charged offense is then required to be proven “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Texas law protects the presumption of innocence for those accused of crimes by explicitly stating: “The fact that [a defendant] has been arrested, confined, or indicted for, or otherwise charged with, the offense gives rise to no inference of guilt at his trial.”

Despite the relaxed factual standards required to warrant a criminal complaint, the Chronicle’s coverage of crime has overwhelmingly focused on the front end of the process. In this phase, the only sources available to determine the truth or falsity of the allegations in the complaint are interested stakeholders (District Attorney, law enforcement, the defendant, and the defendant’s attorneys) who have reviewed the factual allegations included. It is only after the case proceeds past probable cause that the court’s “fact finding” role takes over and the evidence is reviewed through the lens of presumed innocence with a higher standard of proof: “guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.” In our review of the Chronicle’s stories, we found 196 of 219 ‘defendant’ articles (89 percent) to be focused on the allegation(s), rather than the disposition, of a criminal case. In focusing news coverage on as-of-yet unproven allegations, the Chronicle opts to provide coverage at the point in the case when the sources of information are law enforcement and the District Attorney’s Office, two stakeholders with an incentive to characterize the accused as undeniably guilty.

Among articles we analyzed about released defendants, 79 percent of those referencing law enforcement and 74 percent of those referencing prosecutors were negatively biased. Crime reporting aimed at relaying facts to inform the public is impossible at this phase of a case because the available information is fundamentally speculative and biased. In publishing stories about these premature cases as a matter of course, the Chronicle misrepresents the complexity of the criminal process and reinforces the notion that arrest indicates guilt, while also providing little news value.

Of the 270 unique Harris County charges identified in analyzed articles, more than 30 percent of the charges (83 of 270) were ultimately dismissed. The number of dismissals is nearly double the 18.1 percent of Chronicle-covered charges resolved by a guilty plea or a jury verdict (49 of 270), and nearly ten times the 3.7 percent of cases resolved by deferred adjudication or deferred prosecution through probation (10 of 270). The high number of dismissals relative to convictions in these articles is concerning enough, but perhaps the most disturbing statistic concerning the Chronicle’s crime coverage is that 44.4 percent of the criminal charges printed (120 of 270) had not yet reached a disposition. Put another way, nearly half of the charges and factual allegations that the Chronicle saw fit to print came at a time when the court was still fact-finding about those charges—putting their reporters at a factual disadvantage and ultimately misleading its audience. Though dismissals were only 30 percent of the charges covered by the Chronicle, over 57 percent of the 92,354 cases disposed of in Harris County’s criminal courts in 2021 were dismissed.

See the Appendix for 2021 reports for district and county-level courts.

Interested Sources & Failure to Disclose

Attribution is a fundamental journalistic principle, and journalists use attribution—citing their sources of information—to signal the reliability of their reporting. Best practices for attribution are emphasized in most guidelines for ethical journalism, which stress the importance of ensuring the reliability of sources and communicating that credibility to readers. This entails disclosing all available information about a source, including the motivations, bias, and conflicts of interest that a source may have, for “doing so is part of telling the truth, which is a key way that journalists serve their audiences.”

In Part I of this series, we identified sources of bias in media coverage of bond, demonstrating the extent to which bias in coverage is driven by reporters’ use of sources. We showed that the sources that journalists rely on for crime coverage are typically those that have a stake in the criminal process against the accused. While the incentives of law enforcement and the District Attorney’s Office in the criminal process are more apparent, we pointed to Crime Stoppers as an example of a source that is interested in ways not commonly known by the public. In fact, Crime Stoppers has a financial stake in the criminal legal system, given that the organization receives a portion of all court fees required of criminal defendants.

Though Crime Stoppers was not cited by the Houston Chronicle as frequently as it was cited by the television stations reviewed in Part I, a recent uptick in articles referencing Crime Stoppers attests to the organization’s growing influence. From 2015 through 2020 (a 6-year span), the Chronicle referenced Crime Stoppers in 5 total articles; in 2021 alone, Crime Stoppers was referenced in 9 articles. Given that the organization stands to benefit from punitive policies, it is problematic that Crime Stoppers is cited by journalists without any acknowledgement of the motivations that underlie the organization’s commentary. Crime Stoppers of Houston’s financial embeddedness in the criminal legal system expands beyond its remittance of criminal court fees; the organization enjoys financial ties to law enforcement agencies and the District Attorney’s Office. Crime Stoppers annually reports in-kind donations from the Houston Police Department worth over a million dollars, and in September 2021, the organization announced a $500,000 donation that had been pledged by District Attorney Kim Ogg’s office in May 2021. These donations reinforce the notion that Crime Stoppers is politically aligned with law enforcement and the District Attorney’s Office, and it suggests that the organization shares in the motivations and incentives of these groups—especially given Kim Ogg’s service as Executive Director of Crime Stoppers of Houston from 1999 to 2006.

The sources of Crime Stoppers’ funding are reason enough to question the organization’s motives within the criminal justice policy discourse, representing a source of bias that places it firmly in favor of the historical “tough on crime” approach in Harris County. Journalistic transparency demands that this interest be disclosed alongside any attribution to Crime Stoppers, particularly when lending support to the positions of law enforcement or the District Attorney’s Office.

Misrepresentation of the Criminal Legal System: Racial Bias, Sensationalism, False Trends

Crime coverage may not only misinform the public about individual cases and their outcomes, but it can also impart a distorted portrayal of crime, criminal activity, and the scope of the criminal legal system. Covering crime typically involves selecting a few stories for coverage from the vast array of criminal cases transpiring on any given day. In drawing the public’s attention to one incident among many, the selection of a case for coverage bears significant weight. Because the public relies on the media for its knowledge about crime and the criminal legal system, the cases covered in the news can become representative of the entire system in the public consciousness.

In conducting this analysis, we observed several trends in the Houston Chronicle’s coverage of crime—stemming from reporters’ decisions about which stories to cover, which details to highlight, and which cases to construe as part of a “trend”—that constitute an active misrepresentation of Harris County’s criminal legal system, with implications for the public’s perception of bond and pretrial release.

Breaking crime coverage constructs a specific image of crime and criminal identity; by deeming certain alleged crimes worthy of our attention, reporters communicate to readers who and what should be feared. Articles covering criminal allegations frequently feature a mugshot of the accused, a practice that is consequential not only for its public identification of the defendant, but also because it links a criminal incident to the race of the alleged perpetrator. To understand the racial trends in criminal activity as communicated by the Chronicle, we used the Harris County District Clerk’s online court records to identify the race of each defendant named in the Chronicle’s news coverage. We found that 47 percent of articles focused on at least one white defendant (the Clerk’s records do not record ethnicity), 42 percent focused on at least one Black defendant, and 11 percent focused on defendants whose race could not be identified. Given that the population of Harris County is only 20 percent Black, it is clear that Black defendants are vastly overrepresented in the Chronicle’s coverage of criminal defendants.

It is important to further unpack the implications of racial representation in the media’s crime coverage. One might argue that it is unreasonable to expect the media’s coverage of defendants to reflect the racial demographics of the county when Black individuals are overrepresented in the population of criminal defendants; in other words, perhaps we cannot fault the media for simply mirroring the racial bias inherent in our deeply racist criminal legal system. This view ignores the critical role played by the media in generating and reinforcing the racial stereotypes—particularly those linked to criminality and dangerousness—that breed racial bias. Empirical research confirms that the media’s racially distorted coverage of crime causes news consumers to link the threat of crime to racial minorities. Decisions about which crime stories are newsworthy frequently reinforce a racialized narrative of criminality in which Black individuals are rendered disproportionately visible as the perpetrators of crime. In calling attention to criminal cases involving Black individuals, reporters reinforce the stereotype of Black criminality, bolstering the racial bias that generates disproportionate racial outcomes in the criminal legal system.

Reporters also distort the impact of pretrial release by elevating stories about individuals who are arrested for new charges while released on bond. Research on crime coverage suggests that the criminal cases deemed newsworthy by reporters are usually those that are the most statistically rare. The media tends to focus on these extreme cases because their novelty captures the public’s attention. Therefore, not only do reporters needlessly emphasize bond status in stories about criminal allegations, but they also seemingly select stories for coverage that involve released defendants under the pretense that bond status itself makes the story more newsworthy. In doing so, reporters exaggerate the frequency at which defendants released pretrial are arrested for additional crimes. We identified 32 articles where the words “bond” or “bail” were mentioned in the headline of an article, demonstrating the extent to which bond status is emphasized as an issue in crime coverage. Our analysis also revealed the frequency at which reporters exaggerate the impact of a bond-related case by publishing multiple stories about the same defendant. Of the 110 unique defendants named in Chronicle articles, 41 were the subject of multiple articles. This sensationalist amplification, when paired with “availability bias”—the tendency to assume that examples of an issue that readily come to mind are more representative than in reality—ensures that exposure to this type of story will negatively impact a person’s perception of bond reform and pretrial release.

While some crime coverage amplifies the impact of individual cases, other coverage creates the illusion of a “trend” in crime where none exists. One such example is this article by Samantha Ketterer, published in the Chronicle in August 2021. In the article, Ketterer investigates defendants released on bond who were facing seven or more charges, reporting that 141 such defendants were released on bond and that two of these defendants had subsequently been charged with homicides. Several aforementioned issues problematize the reporting in this article—including its failure to mention that pretrial release is a constitutional right in most cases, as well as its lack of acknowledgement that charges, no matter how numerous, do not indicate guilt—but the most pressing issue is the article’s reliance on an arbitrary number of cases to signify a systemic failure.

The sheer volume of criminal cases currently pending in Harris County limits the informational value of singling out small groups of cases sharing the same characteristics, particularly under the premise of exposing a widespread issue. According to Texas’ Office of Court Administration (OCA), over 128,000 criminal cases were pending in Harris County in August 2021. This means the “trend” that Ketterer is reporting on represents less than one-tenth of one percent of all criminal cases. Bearing in mind that Ketterer frames the problem in terms of criminal charges and not convictions, it is also relevant to note that in August 2021, Harris County's criminal courts reported 5,889 dismissals—nearly three times the number of convictions reported that same month.

See the Appendix for August 2021 OCA reports for district and county-level courts.

Spotlight on Harris County Cases

The detrimental impact of the Houston Chronicle’s crime coverage is best demonstrated through an examination of its coverage of specific cases. As previously mentioned, a focus on front-end allegations often leads to inaccurate reporting in the Chronicle.

In one case, the Chronicle published five stories in less than 10 days about Amber Willemsen, a woman suspected of a drunk driving accident that killed a Pearland police officer. Each of these stories mentioned that Willemsen was out on bond for a drug charge (ultimately dismissed) at the time of the crash without any explanation as to why that allegation was relevant to the extant charges. Responding to the blitz of negative coverage around the case, Willemsen’s defense attorney articulated how this type of coverage taints the process and tramples on the rights of the accused: “Without a doubt, Officer Ekpanya’s loss leaves a void in the lives of his loved ones, his colleagues, and citizens he served. Such an untimely death spawns as much outrage as grief, and we naturally rush to judgment. Nonetheless, Ms. Willemsen deserves the benefit of a full, independent investigation and a vigorous legal defense. We do not dignify the memory of one we have lost by forgetting the rights of another.”

Notwithstanding the voluminous negative coverage of Willemsen’s case prior to trial, the Chronicle deserves credit for printing the above comment from her attorney and devoting a significant amount of coverage to her trial and ultimate conviction. Unfortunately, the Chronicle’s coverage of Willemsen’s case from start to finish is more the exception than the rule, with most individual cases only receiving attention at the front end of the criminal legal process, where there is no shortage of salacious allegations to be printed. The pratfalls of this type of coverage can be demonstrated by starting with the outcome or disposition of two specific cases and working backwards to the Chronicle’s early coverage of it.

Tyrin Robertson

Consider the case of Tyrin Robertson, who was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon on June 5, 2017. On August 6, 2018, the District Attorney dismissed the charge, having refiled the case as a murder charge on April 19, 2018. On August 29, 2019, the District Attorney dismissed the murder charge, citing a lack of available witnesses as evidence to the charge. All told, it took the system more than two years to determine that there was not enough evidence to prove Robertson’s guilt. Ultimately, this seems like a true miscarriage of justice; Robertson’s life would never be the same, despite the District Attorney’s dismissal of the charges and the lack of evidence of his guilt.

Given the outcome of the case, one would suspect that the Chronicle’s coverage of the charges revolved around their flimsy nature and the impact that the ultimately dismissed charges would have on Robertson’s life. Unfortunately, the Chronicle’s insistence on covering the front end of the criminal legal process painted a picture that grossly misinformed its readers so egregiously that it is hard to interpret as unintentional.

The Chronicle’s coverage of Robertson’s case started on June 6, 2017—the day after the District Attorney brought initial charges. Reporter Margaret Kadifa’s article prominently featured Robertson’s mugshot before detailing that he was out on bond on unrelated charges (without explaining the relevance of those charges to the incident at hand) and citing “Deputies” who believed that Robertson was armed. The article closed by wording the allegations to read as fact. On June 12, 2017, six days after the first article concerning this case, Kadifa published an update after Robertson was arrested and taken into custody. The update was nearly identical to the initial story on Robertson, detailing that he was released on bond on unrelated charges without explaining their relevance to the case and reprinting allegations from anonymous “deputies” within the Harris County Sheriff’s Office.

June 12, 2017, would be the last time that the Chronicle covered Robertson’s case. As a result, the Chronicle’s reading audience remains unaware that the District Attorney dragged this case out for over a year before upgrading the charges to murder, then took an additional year before ultimately dismissing the murder charges for lack of evidence. The difficulties that Robertson undoubtedly faced (and will continue to face) as a result of having his mugshot and these unproven allegations printed in the newspaper of record cannot be understated, as allegations like these can detrimentally impact someone’s ability to keep a job, housing, or custody of their children, even if the case is dismissed.

In addition to contributing to an immensely negative impact on Robertson’s life, the Chronicle seems insistent on covering only the front end of the process, completely corrupting the journalistic record of reported-on cases and painting an entirely inaccurate picture for its reading audience. Rather than a story about the realities of this case—that the initial allegations could not be corroborated, that it was an ultimately failed prosecution from a District Attorney’s office that has consistently demanded increased resources, that this case contributed to the increasing proportion of dismissals in Harris County’s criminal courts, or that the real perpetrator of this crime was never identified or prosecuted for their actions—Chronicle readers received a double dose of misinformation about Robertson from “sources” (unnamed Sheriff’s deputies) with the incentive to overstate the case against him.

Colby Bankhead

Despite its omission in the Chronicle’s crime coverage, the distinction between the evidentiary standards of probable cause and guilt beyond reasonable doubt is not a trivial one, and in no case is this more apparent than that of Colby Bankhead. As with Robertson’s case, it is helpful to start with the outcome of Bankhead’s case and work backwards to show how egregious the Chronicle’s errors were.

Bankhead was charged on May 17, 2019, with endangering a child and promoting prostitution. The felony charge for endangering a child was dismissed over two years later in July 2021, while the felony charge for promoting prostitution was dismissed in August 2021, having been refiled as felony solicitation of prostitution on April 8, 2021. The charge for solicitation of prostitution was ultimately dismissed later in August 2021, the same month as the charge for endangering a child.

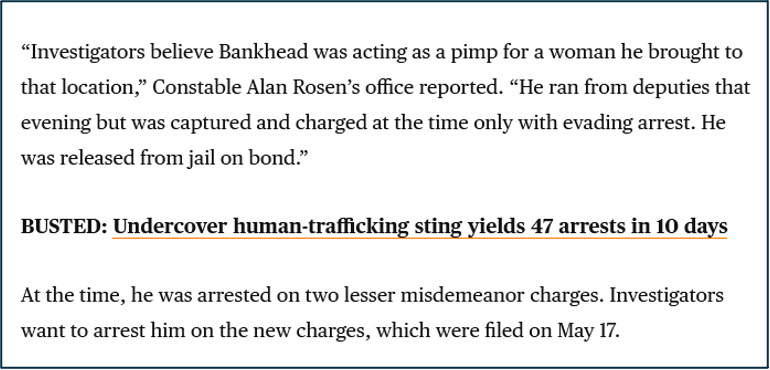

The Chronicle’s first article about Mr. Bankhead was reported by Roy Kent on May 21, 2019. The article detailed the charges against Bankhead, including attribution of key details reported by Constable Alan Rosen’s office without mentioning the Constable’s interest in this case. After describing Bankhead’s criminal history, Kent revealed that Bankhead had been released on bond when he last faced charges and that he currently resided in the Fifth Ward—all without context or explanation about why this was newsworthy or how Bankhead’s history or neighborhood related to the present charges. Bankhead’s mugshot was featured prominently at the top of the article.

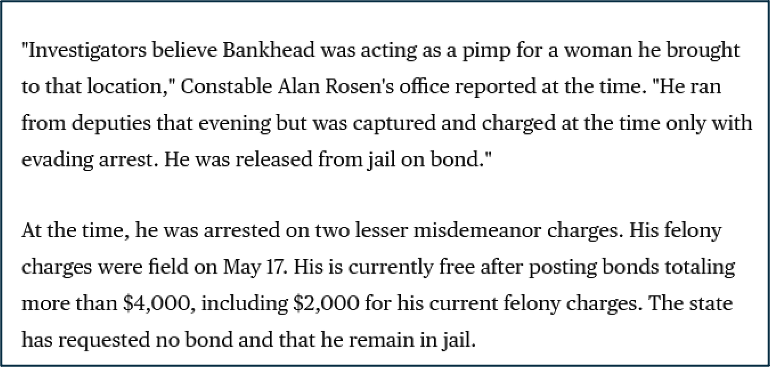

After Bankhead turned himself in to face these charges, Kent reported a follow-up article for the Chronicle on June 19, 2019. This was virtually identical to the first, with the sections detailing Bankhead’s past charges appearing to be copied and pasted from that initial article. Once again, insinuations of Bankhead’s guilt were sourced to the Constable’s Office (no specific individual), and once again Kent felt it newsworthy to publish that Bankhead resided in the Fifth Ward.

Article published on May 21, 2019

Article published on June 19, 2019

These nearly identical articles, written within 30 days of each other, represent the entirety of the Chronicle’s coverage of Bankhead, leaving readers in the dark about the fact that the charges covered so feverishly were, like Robinson’s, ultimately dismissed for lack of evidence.

The Chronicle’s failure to offer continuing coverage on the outcome of many cases means there are likely hundreds if not thousands of innocent individuals impacted by inadequate (and therefore harmful) reporting. In the cases of Robinson and Bankhead, the Chronicle’s coverage actively misinformed its readers, sowing fear and distrust of innocent individuals, and preventing legally innocent individuals from escaping the stigma associated with an arrest.

These cases also show that the implications of the Chronicle’s crime coverage, while drastic for people accused of a crime, are not so for people in law enforcement or the District Attorney’s Office—those who consistently pop up as unnamed sources, assuring the Chronicle’s reading audience of an individual’s guilt. This clearly incentivizes law enforcement and the District Attorney to perpetuate the Chronicle model of crime coverage by continuing to feed reporters stories with salacious allegations, yet discussion of these incentives is notably absent from any of the Chronicle’s coverage.

In Bankhead’s case, both dismissal orders contained the following sentence: “Probable cause exists, but [the] case cannot be proven beyond a reasonable doubt….” If the criminal courts of Harris County determine that insufficient evidence exists to prove an individual’s guilt, it is an extremely important example of the flaws rampant throughout the criminal system. Countless lives have been detrimentally affected by the type of coverage being perpetuated by the Chronicle—coverage that ostensibly requires less work than reporting through the resolution of a case. It is long past time for the Houston Chronicle to start covering the criminal legal system with accuracy, not sensationalism, as its guiding principle.

Conclusion

The Houston Chronicle is to be credited for its balanced coverage of the O’Donnell litigation and the subsequent federal court order; reporters appropriately included voices from both sides of the debate and frequently highlighted the arguments made by each side in their pleadings. Unfortunately, the Chronicle’s coverage of this litigation was in stark contrast to its coverage of individual criminal cases and defendants, which skewed heavily negative. In those instances, the Chronicle frequently relied on practices that served to mislead, rather than inform, its reading audience.

For instance, our analysis reveals that the Chronicle’s coverage of criminal cases contained a disproportionate number of Black defendants compared to the makeup of Harris County’s general population.

Moreover, most of the Chronicle’s crime coverage can be sourced to either law enforcement or the District Attorney’s Office, two parties with a vested interest in the outcome of criminal cases. When not quoting those sources, Chronicle reporters frequently rely on organizations like Crime Stoppers of Houston, the former employer of District Attorney Kim Ogg, which regularly receives hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations from the District Attorney and law enforcement agencies.

Our analysis shows these sources to be frequently inaccurate: Of the 270 unique Harris County charges that we identified in the Chronicle’s crime coverage, nearly a third of charges were ultimately dismissed, while almost half had not yet reached a disposition at the time of our analysis, rendering nearly three quarters of the Chronicle’s coverage of allegations against individuals at best premature and at worst factually inaccurate. The issues posed to defendants by these practices are exacerbated by the fact that Chronicle reporters fail to follow up when a case is disposed. The Chronicle’s approach to articles through this editorial lens leaves its reading audience in the dark about the recent, dramatic increase in dismissals in Harris County’s felony courts—a fact that is rarely, if ever, mentioned by Chronicle reporters.

Many media outlets have re-assessed the nature of their crime coverage since the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department in the summer of 2020. Our analysis shows that, despite balanced coverage of the O’Donnell litigation, sloppy crime reporting persists at the Houston Chronicle. Absent an overhaul in reporting standards with respect to these cases, the Chronicle’s reading audience should view any such reporting with extreme skepticism.

Recommendations

- To avoid perpetuating racial stereotypes about criminality, reporters should stop publishing mugshots of the accused. The practice of posting mugshots draws a link between crime and the race of alleged perpetrators. Because criminal cases involving Black defendants are subject to disproportionate coverage in the media, mugshots reinforce racial bias by attaching Black faces to criminal activity.

- Reporters should refrain from detailing a defendant’s criminal history or bond status absent an explanation of its relevance to the covered case. Highlighting a defendant’s past charges implies that previous arrests indicate guilt or dangerousness. These details risk conflating arrest with guilt and link bond release with negative outcomes.

- To provide a more informative and accurate portrayal of crime and the criminal legal system, reporters should shift coverage from arrests and allegations towards trials and case outcomes. High dismissal rates in Harris County call into question the utility of covering criminal allegations; many defendants covered by the media are not ultimately found guilty. At the very least, reporters should provide follow-up coverage on the outcomes of cases covered prematurely. But to best inform the public, crime coverage should focus on systemic issues rather than breaking crime.

- In covering crime, reporters should adhere to journalistic standards for source attribution, ensuring that sources are credible and disclosing any motivations or conflicts of interest they may have. Coverage should not rely on police and prosecutors as sole sources of information, given that these actors are motivated to portray the accused as guilty. If interested sources are attributed, reporters should disclose their potential conflicts of interest. Furthermore, information about alleged crimes should not be attributed to anonymous sources unless absolutely necessary, nor should they be attributed to vague sources such as “offices” rather than individuals.

Methodology

We conducted a content analysis of 499 news articles published by the Houston Chronicle from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2021. While bias in coverage was the primary focus of this analysis, we also reviewed 13 other key variables, such as referenced sources and the defendant’s race. Listed below are additional details about each element of the analysis.

Sample

We selected news articles for this analysis from the Houston Chronicle’s website. We found articles by searching the website for the keywords “bail” and “bond.” Stories qualified for selection if they discussed bond reform, bond debates, and/or individuals who allegedly committed additional crimes while released on bond. Stories were not qualified for selection if they simply mentioned bond assignments in high-profile cases. We also did not include stories that simply mentioned “bail reform” or “bond reform,” such as those that listed bail or bond reform as part of a political candidate’s platform, but we did include articles that involved any more discussion of the topic beyond just a mention. We did not include letters to the editor in our sample of opinion articles.

Coding

Two people conducted the coding for this analysis. We considered 13 variables as key for the analysis, while 5 others were used to provide logistical information. Once the initial coding process concluded, we audited the variables for accuracy.

Key Variables

- “Article Type” refers to whether the article was categorized as a “defendant,” “bond reform,” or “opinion” article. Coding an article as “defendant” means it is primarily about an individual who was rearrested while released on bond. Coding an article as “bond reform” means it discussed bond reform, policies, or practices. Coding an article as “opinion” means it was published in the opinion section of the Chronicle, including articles written by the Editorial Board.

- “Type of Coverage” refers to the type of bias in an article, if any. Coding terms for this variable include: “Positive,” “Negative,” “Balanced,” and “Neutral.” Coding an article as “Positive” or “Negative” depended on the overall article tone, on which outside sources were used to provide commentary in the article, and which ‘side’ of the bond reform debate received more space in the article. Articles coded as “Positive” indicated a positive bias (in favor of bond reform), while those coded as “Negative” indicated a negative bias (against bond reform). Because some articles discussed regressive bond reform legislation and others discussed bond policies in general, we assessed whether the article was supportive of pretrial release in determining whether the article was positive or negative; in other words, positive articles were in favor of pretrial release, whereas negative articles opposed pretrial release. The presence of bias does not necessarily reflect an internal check for inaccurate information—though negative bias often overlaps with the use of inaccurate information. If the article maintained a neutral tone and offered equal space to both ‘sides’ of the debate, we coded it as “Balanced.” If the article mentioned bond reform or defendants who allegedly committed a crime while released on bond without providing outside commentary, debate points, or a slanted tone, we coded it as “Neutral.”

- “Bail/Bond in Headline” refers to whether or not the words “bail” or “bond” were present in the headline of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.”

- “Allegations” refers to whether or not the article focused on allegations in a criminal case rather than the disposition of a case. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.” We coded an article as “Yes” if it was written about a criminal case prior to the case’s disposition. We coded an article as “No” if it discussed conviction or sentencing in a case, or any other updates post-conviction.

- “Law Enforcement Referenced” refers to whether or not a law enforcement official is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.”

- “CS/Kahan Referenced” refers to whether or not Crime Stoppers (CS) or one of their spokespeople—specifically Andy Kahan—is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. We did not select articles that simply mentioned or included the name Crime Stoppers or their tip line. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.”

- “Police Union Referenced” refers to whether or not a police union—or other law enforcement union—or one of their spokespeople is referenced to provide either commentary on bond reform or details about a case. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.”

- “Mention Judges” refers to whether a local district or felony court judge(s) is mentioned by name in the article. We did not consider federal judges or county judges. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Judge’s Name]” and “Unmentioned.”

- “Mugshot/Picture Included” refers to whether or not a mugshot(s) or mugshot-like picture(s) is used in the article. Coding terms for this variable include: “Yes” and “No.”

- “Defendant Name” refers to the name of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Defendant’s Name],” “Unknown,” and “N/A.”

- “Defendant Race” refers to the race of the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “White,” “Non-White,” “Unknown,” and “N/A.” After the initial coding, we searched for defendants by name on the Harris County District Clerk’s website to confirm their recorded race; Harris County does not record defendant ethnicity, so only race was used. Following confirmation, coding terms include: “Asian,” “Black,” “Indigenous,” “White,” “Unknown,” and “N/A.”

- “Defendant Bond” refers to the kind of bond that was received by the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. Coding terms for this variable include: “monetary,” “general order,” “PR Bond” [personal recognizance bond], and “unmentioned.” If applicable, we coded multiple bond types. An article was coded as “monetary” if it listed a dollar amount associated with a bond. If the article mentioned that the defendant’s bond was “general order” or a “PR Bond” we coded accordingly. If the type of bond was not mentioned, we coded “unmentioned.”

- “Defendant Offense” refers to the offense that was allegedly committed by the defendant(s) that is the subject of an article. The alleged offense can refer to a past offense, the offense that led to a bond assignment, or the offense that the defendant(s) may have committed while released on bond. Coding terms for this variable include: “[Offense Name],” “Unclear,” “N/A (suspect killed by police),” and “N/A.”

Other Variables

- “Article Link”

- “Reporter Name(s)”

- “Publishing Date”

- “Publishing Month”

- “Notes” provides a chance for coders to note any unique article details or requests for other coders.

Methodology for Our Analysis of Dismissals

Using the Harris County District Clerk’s online database, we looked up case records for each defendant identified in a news article as being on bond; we identified a total of 110 defendants who were named in the sample of articles. We then determined which charges were filed against each defendant before they were released on bond (“pre-bond charges”) and after they were released on bond (“post-bond charges”), using the publishing date of the news article as a reference. We identified post-bond charge(s) as any charge(s) filed against the defendant within 2 weeks of the article publishing date. We subsequently identified pre-release charges as the charge(s) filed against the defendant that chronologically preceded the post-release charge(s). In recording pre-bond charges, we included multiple charges if they were filed on the same date, but we did not include all charges filed against the defendant before their release on bond. We then noted whether each charge had been disposed or was still pending. If the case was disposed, we noted whether it was dismissed. We performed this analysis in February 2022.